| Home Page | Local History | Previous | Next | Contact Me |

THE SIX BELLS

|

|

|

“Memories are like leaves of gold, they never tarnish or grow old” |

June 1960 had been a particularly warm and sunny month, with a hot spell following a cooler and changeable second week. Later, violent thunderstorms broke out around the UK, with the West Midlands experiencing 8 hours of continuous thunder, Duns Tew Manor in Oxfordshire seeing 100mm of rainfall in just over 5 hours, and more than 7,000 lightning strikes being recorded at Woolhampton in Berkshire.

On the bright sunny morning of Tuesday 28 June, just a few days after those memorable storms had subsided, the day had begun like any other for several hundred of the colliers employed at the National Coal Board’s Arrael Griffin Colliery at Six Bells, located just south of Abertillery in Monmouthshire. There were 48 miners engaged in maintenance and repair work in the west district, where there would usually have been 123 men working that vein.

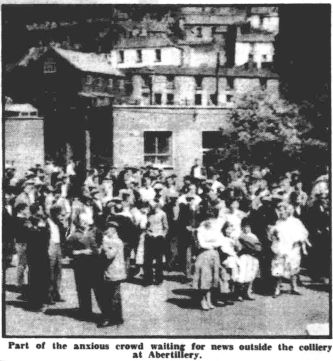

At approximately 10:45am, an ignition of firedamp at a depth of about 354 yards caused an explosion which tore through the entire West district. The pit’s hooter that was continuously sounded alerted local residents that a serious accident had taken place. The news spread like wildfire, causing frightened families and friends to begin gathering at the colliery, anxiously praying and waiting for news from the rescue teams who had raced to the scene from all parts of the county. But the news was not good.

The explosion was devastating, trapping and killing all but 3 of the miners. Those who lost their lives included twin brothers Billy and Mansel Reynolds, and 3 fathers and their sons, Vernon and Clive Griffiths, Roy and Colin Morgan, and William and Tony Partridge. For the Morgan family, it was a triple tragedy, as Roy’s 26 year-old nephew Colin was also among the victims. The 48 workmates lived in various locations including Aberbeeg, Abertillery, Blaina, Brynmawr, Llanhilleth, Nantyglo, and Six Bells, their ages ranging from 18 to 60. There were very few families without a relative, neighbour, or friend among those injured or killed.

It was at the Arrael Griffin pit that my grandmother’s cousin, Ness Edwards M.P., had been brought up in the mining industry, and many of the dead were among his workmates. My uncle Gwyn, who was working in the Six Bells Colliery offices that fateful morning, told me that various processes were quickly put in place, including compiling a list of those at work at the time from the underground lamp records. The list was then given to the Senior Clerk, Frank Bayton, to provide the miners’ addresses so that the families could be contacted with any news. While working through the list, Frank was confronted by the name of his own brother, Ivor.

Vivian Luther, the 40 year-old Colliery Manager, worked tirelessly for 12 hours directing the rescue teams. It was just after midnight that the grim announcement was made that the bodies of all the missing men had been located, and that none of them had survived. After snatching just an hour of sleep that night, he was back in charge of operations at the pit on Wednesday morning. My cousin, Lynne, who was in school with Vivian and Kathleen Luther’s daughter, vividly remembers her coming into school and telling them that her dad had been crying.

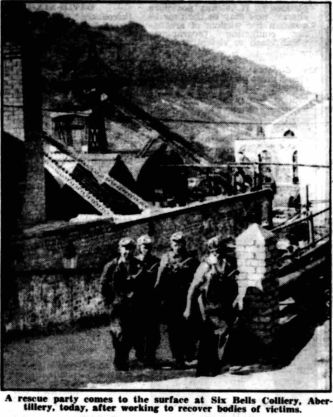

It was that Wednesday afternoon when the last of the bodies were brought to the surface by grimy and tired-eyed rescuers. The victims had been carried one and a quarter miles through passages, past debris which had taken 54 men 12 frantic hours to move. The horror of the scene underground where the bodies were found was described by one of the rescue workers as being “like going through a waxworks.”

|

QUEEN’S MESSAGE |

Roy Brown, one of the victims, was due to sit an important mining examination that Wednesday to continue his successful career. He and his wife had an 18 month-old baby, and would have celebrated their 6th wedding anniversary on Saturday 2 July. Another victim, Trevor Paul, left a wife to mourn his loss, along with a 4 year-old son and a 3 week-old baby. One of the Reynolds twins, Billy, and his wife were expecting their first baby, while plans for a Christmas engagement by 19 year-old Dennis Lane and his girlfriend Eileen were shattered by his tragic death.

Two of the three survivors, Cliff Lewis and Michael Purnell, were taken to the Abertillery & District Hospital. Cliff, the father of a 7 week-old daughter, was later discharged, but Michael had a much longer stay because of severe burns. The third survivor, Harold Legge, was about half a mile from the coal face when the explosion happened. He said: “I heard a roar which it is a job to describe. There was a flash across my eyes and I couldn’t see for dust, I had a job to breathe.” He later discovered that only 20 yards from where he had been working, one of his colleagues had been killed.

For Jim Watkins and Stanley Nash, it had also been a narrow escape. Jim, an electrician, was due to be working in the W district that morning, but was sent to H district which saved his life. Two weeks earlier, Stanley had exchanged work places with Wilfred Phipps. On the morning of the explosion, Stanley was at work in H district, while in the W district Wilfred was one of those killed. A doctor had to be called to Eva Phipps of 32 Aberbeeg Road, Wilfred’s 82 year-old mother, who collapsed with shock after hearing of her son’s death. Also fortunate was Colin Townsend, of Carlisle Street, Abertillery. It was his 18th birthday that day, and he had been persuaded by his parents not to go to work. A neighbour said: “When his mother heard of the explosion she cried with relief.”

On Thursday 30 June, a number of men were selected to descend the 1,000 feet shaft to complete necessary ventilation work. They were later followed by experts from the Safety in Mines Research Establishment, based at Buxton in Derbyshire, who began a complete and thorough examination of the area where the explosion took place. The inquest into the disaster was officially opened the same day, which concentrated on formally identifying the bodies of the victims, after which the inquest was adjourned. Kenneth Treasure, the Coroner for Monmouthshire, stated: “Although this is now a valley of the shadow I hope It will not be long before it will pass and the sun shines once more.” He also said that “the whole nation feels for the relatives of the victims in this moment of tragic sadness.” This soon became apparent by the South Wales Gazette’s regular updates on how generous aid was pouring in from near and far, both at home and from overseas. In fact, in less than 4 months, over £93,000 had been raised for the Six Bells Colliery Disaster Fund, which was sponsored by the Western Mail and the South Wales Echo. When the fund closed on 31 March 1961, the total raised was an incredible £102,456 18s 1d.

On Saturday 2 July, 26 of the victims were buried at the New Cemetery, Brynithel. Several thousand miners from all parts of the South Wales coalfields attended to pay tribute to those who had lost their lives. They lined the route from Six Bells to the mountainside cemetery, located about a mile from the colliery. Thousands more people lined the route or watched from the Arael mountain. The sombre procession of miners, led by representatives of the National Union of Mineworkers, the National Coal Board, and local authorities, marched ahead of the first two coffins. The rest of the coffins were taken in twos at half hourly intervals throughout the day. Funerals of the remaining victims took place at local cemeteries, as well as at the crematoriums at Croesyceiliog and Glyntaff.

In November 1960, it was announced that payments from the Six Bells Colliery Disaster Fund would begin to be made on a weekly basis before Christmas. Widows would receive a total of £90 per year, while children up to the age of 16 would receive £67 10s per year, and a special provision was also made for those who continued in full-time education after that age. Widows who re-married would stop receiving weekly payments, but would receive a one-off payment of £250 on re-marriage. They would not generally be able to receive payments again from the fund after a subsequent widowhood. A provision was also made for dependant families in cases of hardship.

On Wednesday 15 February 1961, after a number of adjournments and more than 7 months following the disaster, the verdict was finally given: “Accidental death.”

The following pages contain details of the 45 victims, 3 survivors, and other personnel, and has been arranged by their date of birth, from the oldest to the youngest. The memorial notices and inscriptions that appear after many of them were found in newspapers, books of remembrance, and on gravestones.

CREDITS

The photo of “The Guardian” at Six Bells is a Flickr photo by Darryl Hughes The statue stands 20 metres high, and overlooks Parc Arael Griffin in Six Bells, the landscaped area where the Colliery once stood. It was designed and created by Sebastien Boyesen, and was unveiled in 2010 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the disaster.

The photos of the anxious crowd at Six Bells and part of the rescue team are edited from the Coventry Evening Telegraph of Wednesday 29 June 1960. They are Copyright by D.C. Thomson & Co. Ltd., and were created courtesy of The British Library Board.